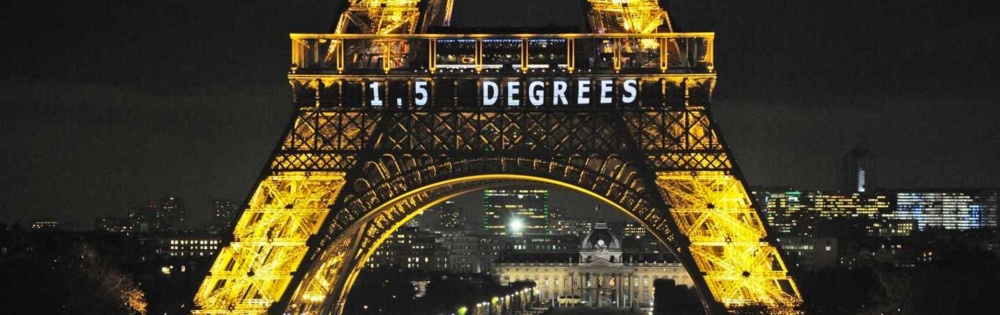

The river basins of the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra in South Asia are seen as climate change hotspots. These river basins, which are largely fed by mountain water are home to a population around 900 million people, which is likely to increase to al 1 billion halfway the 21st century. Climate change is expected to hit hard in this region which is already facing natural disasters like floods, droughts, landslides and heat waves. Last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change finalized its special report “Global Warming of 1.5 °C”, in response to the signing of the “Paris Agreement” in 2015, where the global mutual aim to limit global temperature increase to 1.5 °C was stipulated. The report outlines the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. A team of researchers of the HI-AWARE consortium, led by Arthur Lutz (FutureWater) published a study trying to answer the question: “What would a 1.5 °C global temperature increase imply for the South Asian river basins?”

They did this by analyzing climate model data for changes in a range of climate change indicators over the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins. For example, they looked at changes in rainfall patterns over the seasons, but also at changes in extreme rainfall events, which are a key driver of floods and landslides. Similarly they examined future changes in drought and heat extremes.

One of the findings is that a global temperature increase of 1.5 degrees would imply a regional temperature increase of more than 2 degrees. The culprit here is the fact that mountainous areas tend to warm up much faster than low-lying lands, a process also referred to as “elevation-dependent warming”. With the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayan mountain ranges as the basins’ headwaters, this phenomenon is particularly strong for South Asia. They also showed that 1 degree of global temperature increase with respect to preindustrial levels has already been realized to date.

The analysis of climate change indicators shows that the impacts of a continuation of the global warming to the 1.5 degrees level are significant. For example, monsoon precipitation increases by 3 to 11% and the intensity of extreme rainfall events increases by 7-11%. Also, the number of nights with very high nighttime temperature, hampering sufficient cooling of the human body, would increase by around 10% on average. Other climate scenarios, which may be more likely if the current pace of warming continues, were also analyzed. These scenarios would lead to a regional warming of 3.4 to 5.8 °C at the end of the 21st century compared to preindustrial levels. With that, other adverse effects of climate change would be worse. For example, the intensity of extreme rainfall events could increase by up to 50%.

Earlier, FutureWater contributed to research showing that Asia’s glaciers would lose around one third of their present-day ice mass by the end of the century. This loss could be up to two-thirds at higher global warming scenarios. These changes will likely lead to strong shifts in timing of water supply from the high mountains, being an important factor to include in water availability scenarios for South Asia.

The team stresses that the full range of climate projections needs to be taken into account to formulate robust climate adaptation policies, and should not be limited to global warming scenarios of 1.5 or 2 degrees. Preparing for 1.5 or even 2 degrees of global warming will probably not be enough.